This Group Has Varied, More Egalitarian, Roles for Women in the Family.

Two Spirit Society of Denver marches at PrideFest Denver, 2011

Traditional gender roles among Native American and Commencement Nations peoples tend to vary profoundly by region and community. Every bit with all Pre-Columbian era societies, historical traditions may or may not reflect contemporary attitudes. In many communities, these things are non discussed with outsiders.

Apache [edit]

Traditional Apache gender roles have many of the same skills learned by both females and males. All children traditionally learn how to cook, follow tracks, peel leather, sew stitches, ride horses, and utilise weapons.[i] Typically women gather vegetation such as fruits, roots, and seed. Women would often prepare the food. Men would use weapons and tools to chase animals such as buffalos.[2] It is expected that women do not participate in hunting, [3] but her role as a mother is of import. A puberty rite ceremony for young girls is an of import event,[3] hither the daughter accepts her office as a women, and is blest with a long life and fertility.[ii] [4] Apache people typically live in matrilocal households, where a married couple will live with the wife's family.[5]

Eastern Woodland Societies [edit]

Eastern Woodland communities vary widely in whether they divide labor based on sexual activity. In general, similar in the Plains nations, women own the home while men's piece of work may involve more than travel.[6] Narragansett men in farming communities have traditionally helped clear the fields, cultivate the crops and assist with the harvesting, whereas women hold authorization in the habitation.[vii] Amidst the Lenape, men and women have both participated in agriculture and hunting according to historic period and ability, although principal leadership in agronomics traditionally belongs to women, while men have more often than not held more responsibility in the area of hunting. Whether gained by hunting, line-fishing or agriculture, older Lenape women take responsibility for community food distribution. Land management, whether used for hunting or agronomics, also is the traditional responsibility of Lenape women.[viii]

Historically, a number of social norms in Eastern Woodland communities demonstrate a rest of power held between women and men. Men and women have traditionally both had the final say over who they would end up marrying, though parents usually have a great deal of influence also.[9]

Hopi [edit]

The Hopi (in what is at present the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona) are traditionally both matriarchal and matrilineal,[ten] with egalitarian roles in community, and no sense of superiority or inferiority based on sexual practice or gender.[11] Both women and men have traditionally participated in politics and community direction,[12] although colonization has brought patriarchal influences that take seen changes in the traditional structures and formerly-college status of women.[13] However, fifty-fifty with these changes, matrilineal structures nevertheless remain, along with the key role of the mothers and grandmothers in the family, household and clan structure.[14] [xv]

Haudenosaunee [edit]

The Haudenosaunee are a matriarchal order. Traditionally, the Clan Female parent has held the ultimate ability over all decisions, though her specific role has varied by Nation. In this structure the men nether her are the Chiefs, serving primarily in a diplomatic capacity. Tradition holds that she has the power to veto any thought proposed past her chiefs, and that both the naming traditions and transfer of political power are matrilineal. [xvi]

Kalapuya [edit]

The Kalapuya had a patriarchal lodge consisting of bands, or villages, usually led in social and political life by a male person leader or grouping of leaders.[17] The primary leader was by and large the man with the greatest wealth.[18] While female leaders did exist, information technology was more mutual for a woman to gain status in spiritual leadership. Kalapuya bands typically consisted of extended families of related men, their wives, and children.[eighteen] Formalism leaders could be male or female, and spiritual ability was regarded as more valuable than cloth wealth. As such the spiritual leaders were often more than influential than the political leaders.[nineteen]

Kalapuya males usually hunted while the women and immature children gathered food and set upwards camps. As the vast majority of the Kalapuya nutrition consisted largely of gathered food, the women supplied most of the sustenance. Women were also in charge of food grooming, preservation and storage.[20] The food hunted by men usually consisted of deer and elk, and fish from the rivers of the Willamette valley, including salmon and eel. Plants gathered included wapato, tarweed seeds, hazelnuts, and especially camas. The camas bulbs were cooked past women into a block-like bread which was considered valuable. [21]

Women were involved in the customs life and expressed their individual opinions.[20] When a man wanted to ally a woman, he had to pay a helpmate price to her begetter.[22] If a man slept with or raped some other man's married woman, he was required to pay the bride price to the husband. If he did not, he would exist cut on the arm or confront. If the human could pay the toll, he could take the woman to be his wife.[23]

There is reference to gender variant people being accepted in Kalapuya culture. A Kalapuya spiritual person named Ci'mxin is recalled by John B. Hudson in his interviews from the Kalapuya Texts:

They would say "He is a man (in torso), he has inverse to a woman (in dress and manner of life). But he is not a adult female (in body). It is his spirit-ability it is said that has told him, You become adult female. You are always to wear your (woman's) wearing apparel only like women. That is the way you must e'er practise."[24]

After the arrival of Europeans to the Willamette Valley, and creation of the Grand Ronde Reservation and boarding schools such as Chemawa Indian Schoolhouse, children of the Kalapuya people were taught the typical gender roles of Europeans[ vague ].[25]

Inuit [edit]

Arvilingjuarmiut [edit]

The Arvilingjuarmiut, besides known as Netsilik, are Inuit who live mainly in Kugaaruk and Gjoa Haven, Nunavut, Canada. They follow the tradition of kipijuituq, which refers to instances where predominantly biologically male person infants are raised as females. Frequently the decision for an baby to become Kipijuituq is left to the grandparents based on the reactions of the infant in the womb.[26] Children would later on go along to choose their respective genders in their pubescent years in one case they have undergone a rite of passage that includes hunting animals.[26] Similar in concept is sipiniq from the Igloolik and Nunavik areas.[27]

Aranu'tiq [edit]

Aranu'tiq is a fluid category among the Chugach, an Alutiiq people from Alaska, that neither conforms to masculine or feminine categories.[28] Gender expression is fluid and children typically dress in a combination of both masculine and feminine clothing.[28] Newborn babies are non regarded as new humans but rather equally tarnina or inuusia which refers to their soul, personality, shade and are named afterward an older deceased relative equally a way of reincarnation every bit the relationship between the child and others would get on to lucifer those of the deceased.[29]

[edit]

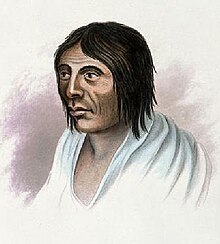

The third gender role of nádleehi (meaning "i who is transformed" or "one who changes"), beyond contemporary Anglo-American definition limits of gender, is office of the Navajo Nation lodge, a "two-spirit" cultural role. The renowned 19th century Navajo artist Hosteen Klah (1849–1896) is an example.[xxx] [31] [32]

Nez Perce [edit]

During the early colonial menses, Nez Perce communities tended to have specific gender roles. Men were responsible for the product of equipment used for hunting, fishing and protection of their communities as well equally the functioning of these activities. Men made upwards the governing bodies of villages which were equanimous of a council and headman.[33] [34] [35]

Nez Perce women in the early on contact period were responsible for maintaining the household which included the production of commonsensical tools for the home. The harvest of medicinal plants was the responsibility of the women in the customs due to their all-encompassing knowledge. Edibles were harvested by both women and children. Women also regularly participated in politics, only due to their responsibilities to their families and medicine gathering, they did not concord office.[33] [34] [35] Critical knowledge regarding civilization and tradition were passed down by all the elders of the community.[33] [34] [35]

Ojibwe [edit]

Historically, most Ojibwe cultures believe that men and women are usually suited towards specific tasks.[36] Hunting is usually a men's task, and first-kill feasts are held as an honour for hunters.[36] The gathering of wild plants is more often a women'due south occupation; however, these tasks often overlapped, with men and women working on the aforementioned projection simply with different duties.[36] Despite hunting itself existence more commonly a male task, women also participate by building lodges, processing hides into clothes, and drying meat. In contemporary Ojibwe civilization, all community members participate in this work, regardless of gender.[36]

Wild rice (Ojibwe: manoomin) harvesting is done by all community members,[37] though oftentimes women will knock the rice grains into the canoe while men paddle and steer the canoe through the reeds.[37] For Ojibwe women, the wild rice harvest tin can be especially significant as it has traditionally been a chance to express their autonomy:[38]

The wild rice harvest was the well-nigh visible expression of women's autonomy in Ojibwe society. Binding rice was an important economical activity for female person workers, who inside their communities expressed prior claims to rice and a legal correct to use wild rice beds in rivers and lakes through this practice. Ojibwe ideas nigh property were not invested in patriarchy, every bit in European legal traditions. Therefore, when early travelers and settlers observed Ethnic women working, it would have involved a paradigm shift for them to capeesh that for the Ojibwe, water was a gendered space where women's formalism responsibleness for water derives from these related legal traditions and economical practices.

—Brenda J. Child, Holding Our World Together, p. 25

While the Ojibwe keep to harvest wild rice by canoe, both men and women now take turns knocking rice grains.[36]

Both Ojibwe men and women create beadwork and music, and maintain the traditions of storytelling and traditional medicine.[37] In regards to clothing, Ojibwe women have historically worn hibernate dresses with leggings and moccasins, while men would wear leggings and breechcloths.[37] After trading with European settlers became more than frequent, the Ojibwe began to prefer characteristics of European dress.[37]

Osage [edit]

Sioux [edit]

The Lakota, Dakota and Nakota peoples, in addition to other Siouan-speaking people like the Omaha, Osage and Ponca, are patriarchal or patrilineal and accept historically had highly defined gender roles.[39] [xl] In such tribes, hereditary leadership would pass through the male line, while children are considered to belong to the father and his clan. If a woman marries outside the tribe, she is no longer considered to be part of it, and her children would share the ethnicity and culture of their father.[xl] In the 19th century, the men customarily harvested wild rice whereas women harvested all other grain (among the Dakota or Santee).[41] The winkte are a social category in Lakota civilisation, of male people who prefer the habiliment, work, and mannerisms that Lakota culture ordinarily considers feminine.[42] Unremarkably winkte are homosexual, and sometimes the word is likewise used for gay men who are not in whatsoever other way gender-variant.[42]

Come across likewise [edit]

- Native Americans in the U.s.a. – Gender roles

- Indigenous feminism

- Matriarchy (the Native Americans subsection)

- Missing and murdered Ethnic women

- Native American feminism

- Patriarchy

- Sexual victimization of Native American women

- Two-Spirit

References [edit]

- ^ 100 Native Americans Who Shaped American History, Juettner, 2007.

- ^ a b "Our Civilisation". Official Website of the Mescalero Apache Tribe . Retrieved 2021-11-06 .

- ^ a b Opler, Morris (1996). An Apache Life-way: The Economic, Social, and Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indian. BISON BOOKS. ISBN0803286104.

- ^ Markstrom, Carol. "Empowerment of Northward American Indian Girls : Ritual Expressions at Puberty". University of Nebraska Press – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Wightman, Abigail. "Honoring Kin: Gender, Kinship, and the Economy of Plains Apache Identity". SHAREOK.

- ^ James Ax tell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford Academy Press, 1981, 107-110

- ^ James Ax tell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford University Printing, 1981, 123

- ^ Gun log Fur, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Amongst the Delaware Indians, Philadelphia, Academy of Pennsylvania Printing, 2009, 87

- ^ James Axtell, The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes, New York, Oxford Academy Press, 1981, 74-75

- ^ Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female person Superiority, in Quarterly Journal of Credo: "A Critique of the Conventional Wisdom", vol. VIII, no. 4, 1984, p. 44 and see pp. 44–52 (essay based partly on "seventeen years of fieldwork amid the Hopi", per p. 44 n. 1) (author of Dep't of Anthropology, Univ. of Ariz., Tucson).

- ^ LeBow, Diana, Rethinking Matriliny Among the Hopi, op. cit., p. [8].

- ^ LeBow, Diana, Rethinking Matriliny Among the Hopi, op. cit., p. eighteen.

- ^ Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, op. cit., p. 44 n. one.

- ^ Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Credo of Female person Superiority, op. cit., p. 45.

- ^ Schlegel, Alice, Hopi Gender Ideology of Female Superiority, op. cit., p. l.

- ^ Thomas, Katsithawi. "Gender Roles among the Iroquois" (PDF).

- ^ Prescott, Cynthia Culver. "Gender and Generation on the Far Western Frontier." Google Books, Google, 2007

- ^ a b Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The Earth of the Kalapuya, pg. 17.

- ^ Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, pg. nineteen.

- ^ a b Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The Earth of the Kalapuya, pg. 20.

- ^ Kramer, Stephanie. "Camas Bulbs, the Kalapuya, and Gender: Exploring Evidence of Plant Food Intensification in the Willamette Valley of Oregon." University of Oregon Scholars Bank, University of Oregon, June 2000,

- ^ Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle, Washington: The University of Washington. pp. 45–46.

- ^ Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle, Washington: The Academy of Washington. p. 44.

- ^ Jacobs, Melville (1945). Kalapuya Texts. Seattle, Washington: The University of Washington. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Juntunen, Dasch, and Rogers, The World of the Kalapuya, pg. 111.

- ^ a b Stewart, Henry, "Kipijuituq in Netsilik Society", Many Faces of Gender, Academy of Calgary Press, pp. 13–26, ISBN978-1-55238-397-1 , retrieved 2021-02-26

- ^ Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (1997). Sinews of Survival: the Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 214. ISBN978-0-7748-5641-6. OCLC 923445644.

- ^ a b author., Saladin d'Anglure, Bernard. Inuit stories of being and rebirth : gender, shamanism, and the third sex. ISBN978-0-88755-559-half dozen. OCLC 1125818726.

- ^ A., Frink, Lisa. Shepard, Rita Due south. Reinhardt, Gregory (2002). Many faces of gender : roles and relationships through time in indigenous northern communities. University Printing of Colorado. ISBN0-87081-677-two. OCLC 49795560.

- ^ Franc Johnson Newcomb (1980-06). Hosteen Klah: Navaho Medicine Human and Sand Painter. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1008-2.

- ^ Lapahie, Harrison, Jr. Hosteen Klah (Sir Left Handed). Lapahie.com. 2001 (retrieved xix Oct 2009)

- ^ Berlo, Janet C. and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-nineteen-284218-3 . pg. 34

- ^ a b c "Gender Roles" at the Nez Perce Museum, United states Department of the Interior, Parks Service; accessed five April 2016

- ^ a b c Colombi, Benedict J. "Salmon and the Adaptive Capacity of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) Culture to Cope with Modify" in the American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Wintertime 2012), pp. 75-97. University of Nebraska Press; accessed 5 April 2016

- ^ a b c "History of CTUIR" at Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation; accessed 5 April 2016

- ^ a b c d e Buffalohead, Priscilla (1983). "Farmers, Warriors, Traders: A Fresh Look at Ojibway Women" (PDF). Minnesota History. 48: 236–244 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e St. Louis County Historical Society (SLCHS). "Lake Superior Ojibwe Gallery" (PDF). 1854 Treaty Authority . Retrieved February 26, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kid, Brenda J. (2013). Holding our globe together : Ojibwe women and the survival of community. Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-14-312159-half dozen. OCLC 795167052.

- ^ Medicine, Beatrice (1985). "Child Socialization amongst Native Americans: The Lakota (Sioux) in Cultural Context". Wicazo Sa Review. 1 (2): 23–28. doi:10.2307/1409119. JSTOR 1409119.

- ^ a b Melvin Randolph Gilmore, "The True Logan Fontenelle", Publications of the Nebraska Country Historical Guild, Vol. 19, edited past Albert Watkins, Nebraska State Historical Society, 1919, p. 64, at GenNet, accessed August 25, 2011

- ^ Jonathan Periam, Habitation and Farm Transmission, 1884, likely citing USDA brief on "Wild Rice".

- ^ a b Medicine, Beatrice (2002). "Directions in Gender Research in American Indian Societies: Two Spirits and Other Categories by Beatrice Medicine". Online Readings in Psychology and Culture (Unit iii, Chapter 2). W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. North. Sattler (Eds.). Center for Cantankerous-Cultural Research, Western Washington University. Archived from the original on 2003-03-thirty. Retrieved 2015-07-07 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_roles_among_the_indigenous_peoples_of_North_America

0 Response to "This Group Has Varied, More Egalitarian, Roles for Women in the Family."

ارسال یک نظر